I recently started reading Classroom of the Elite. I watched the anime around two years ago, but although I enjoyed it, the experience didn’t stick with me. I’m glad I picked up the light novels, though, as even the introductory arc had quite a lot to chew on.

In fact, I’d go as far to say that I was emotionally moved by the story told in these first two volumes, in a way that I didn’t expect at all.

I’m going to discuss these two books in detail, so let’s get to it. SPOILERS AHEAD.

The Purpose of COTE’s First Arc

COTE‘s first two volumes have an obvious purpose: Setting up the characters and premise. They spend a lot of time going through the motions, to the extent that some scenes may feel frivolous and repetitive. Even diehard fans of the series don’t tend to have a lot to say about the first arc, other than that it introduces the school’s hierarchical system while hinting at the protagonist Ayanokouji’s troubled past.

Yet even from the beginning, COTE’s smart writing shines through. The premise of a school where students are defined by their place in an arbitrary hierarchy is a pointed social commentary on Japan’s education system. People like to talk about equality as a platitude, but the harsh truth is that humans aren’t born equal, and there are invisible forces preventing the ideal from becoming reality. The book even begins with a monologue bluntly making that point, just in case it wasn’t clear enough.

That opening monologue is the only occasion when COTE gets on-the-nose with its themes. Everything else the series has to say is expressed organically through the characters and how they react to the system they’re in. This is why it can be easy to overlook just what was so affecting about the opening conflict, which was driven by the class delinquents. At its core, it’s a story about unsympathetic victims who would normally never receive the help or guidance they actually need. But in this story, our main characters band together to help them, because they realise that it’s in everyone’s best interests to do so.

“It’s Your Own Fault You’re In This Mess”

It’s easy to be irritated by Sudou, Ike and Yamauchi. The first two volumes spend a lot of time on their inane conversations, which are mostly defined by them being casually sexist and immature. It’s enough to make you wonder at first why Ayanokouji, who is clearly much more intelligent than they are, hangs out with them.

Things don’t get any better for the Three Stooges when it turns out that their poor academic abilities have dragged the entire class’s evaluation down. What’s worse is that even after they’re confronted with the consequences of their actions, they don’t have any intention of actually improving. “What’s the point of studying?” Sudou asks, because he wants to be a professional basketballer. Meanwhile, Ike insists that he’ll just cram the night before the test and he’ll be fine. Horikita, the most academically gifted student in the class, has no patience for them and their excuses.

Despite how unlikable those three are as people, though, I couldn’t help but sympathise with the position they’re in. They’re stuck in a system where academic results define your entire worth, and it sucks. There are so many kids in the world who are alienated by academics, and trying to force them to fit the mold is like trying to hammer a square peg into a round hole. Sudou has a point when he says that academics are of no use to him, but the world demands this arbitrary knowledge of him anyway.

In the real world, people like the Three Stooges would be left to sink on their own. It’s easy to think, “It’s your own fault you’re in this mess, so why should I bother helping you?” It’s telling that none of their classmates made an effort to intervene during the first month when those boys were at their least motivated. Even though it should have been obvious to everyone that you shouldn’t skip class or sleep during it, nobody lifted a finger to help them for their own good. It’s only when the class learns about the Class Point system do they decide that Sudou and the others should get tutored, but even then…

“…It would be easier for everyone if they just got expelled…”

That’s the despicable thought that occurred to me as I read the book.

Despite considering myself the kind of person who values equality – a socialist, even – I was willing to give up on those guys. After Horikita makes her initial aborted effort to teach them and they refuse to engage, I was like, “Well, okay. You did what you could. There’s no point trying to help people who don’t want to be helped.” When the possibility is brought up that their expulsion would raise the class average, a part of me genuinely thought, “It’s more efficient to just cut them loose than try to turn them into good students.”

It’s clear as day that most of Class D thought the same way as me, even if they were trying to be nice about it. The class’s casual cruelty manifested in inaction rather than outright bullying, and in a way that’s just as bad. It’s terrible to admit to something so cold-hearted, but if you just shrug and do nothing while thinking, “It’s their own problem to deal with anyway,” then you can at least maintain the illusion that you’re one of the good guys. This is the real brilliance of volume 1. By portraying the victims of the system as flawed and messy people, it nudges you to sympathise with a truly awful position.

So when Ayanokouji steps in with a simple yet self-sacrificial means of solving the problem, it was a big eye-opener for me.

By sacrificing his own points, he saves Sudou from expulsion. It’s the moment that affirms the deeply capitalist logic of the system, because you can literally buy test scores with currency, while also revealing that Ayanokouji doesn’t think like most people. He doesn’t believe that people are equal. “…But wouldn’t it be nice to strive for a little more equality?”

The truth is that victims don’t have to be saints or martyrs to be deserving of justice. And pretending otherwise is how ordinary people help perpetuate an unfair system. Short of dismantling the entire system, the least we can do is not blame an individual’s personal failings for the disadvantages beyond their control. By buying a higher score for Sudou, Ayanokouji chooses to give Sudou a better chance within the system. It’s an unexpected show of altruism from a guy who was seemingly detached from everything going on.

The brilliance of the delinquent subplot doesn’t end there. Just when you think the Sudou matter has been resolved, volume 2 opens with him getting into trouble again. This time, he gets framed by members of Class C who are jealous of his basketball skills. It’s the kind of plot development that would make you groan and think, “Again?” Yet it’s a good opportunity to really bring out the nuances of Sudou’s personality and foibles. As the author notes in the afterword, it’s unrealistic to think that his problems would simply end after he passes a single test.

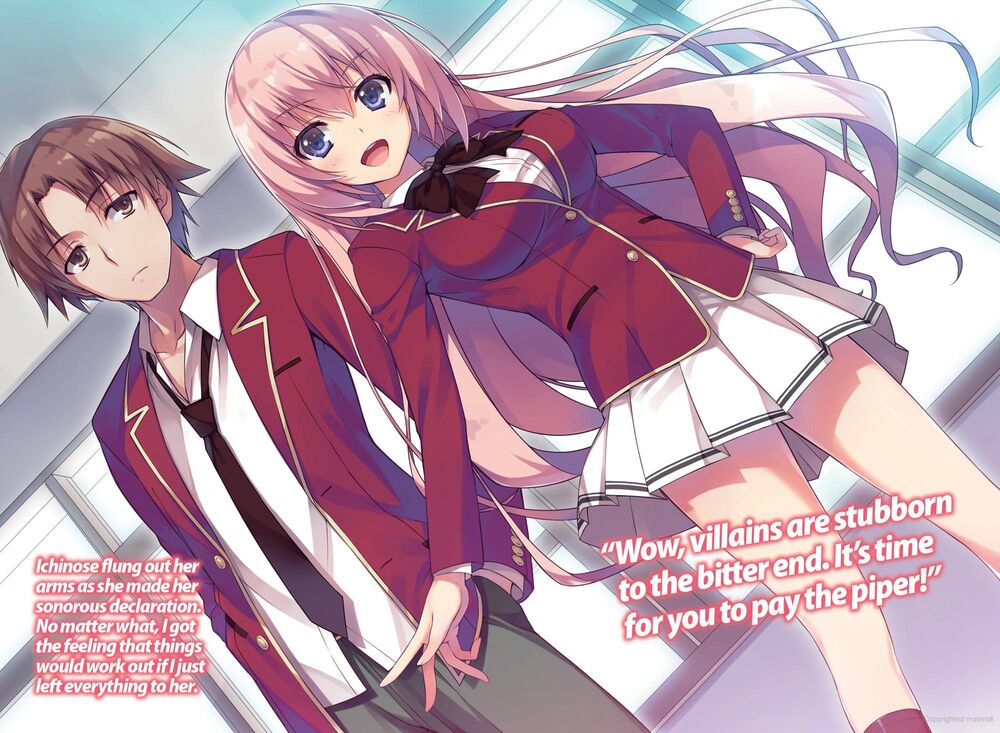

Once again, the story threads the needle by acknowledging personal responsibility alongside factors outside one’s control. Horikita isn’t sympathetic towards Sudou because she thinks that his abrasive personality indirectly brought trouble in his direction. But she still stands up for him anyway, because the fact of the matter is that he was framed for a crime he did not commit. One of the more memorable scenes of volume 2 is when Horikita refuses to accept a reduced punishment for Sudou because she seeks to clear his name completely. That is justice.

An Ideal Unequal System

Volume 2 serves the dual purpose of giving closure to Sudou’s subplot while expanding the scope of the cast and story significantly. This is definitely for the best. If COTE simply repeated the same themes of social inequality, it might have gotten stale. There would have been no point setting it in a school filled with exceptionally gifted children if it was just a microcosm of adult society.

In volume 1’s afterword, Shōgo Kinugasa talked about how his feelings of regret about school fueled the story of Classroom of the Elite. After becoming an adult, he now looks back on school and realises what a limiting environment it was. If only the education system had been more open-minded about the individual aptitudes of students, then it might not have taken him so long to realise such important things about himself.

I believe that Classroom of the Elite is a story about finding the catharsis that a real school doesn’t actually give you.

In the real world, the social hierarchy is “invisible.” There are all sorts of people who like to pretend that it doesn’t exist, or that you can overcome systemic issues with a little bit of individual effort. But in the world of COTE, the system is plainly visible. It’s made abundantly clear that the problems of the minority will also affect the majority, so people should help each other out.

Even as early as volume 2, it’s strongly hinted that people are allocated to Class D if they have “the most room to grow.” In other words, placements aren’t determined by objective measures like academics or athletic achievements, but through narrative contrivance.

“Contrivance” may seem like a negative word, but in this context I mean that as a good thing. The system in COTE resembles the inequalities of the real world, but it’s also arbitrary. It exists so that the students know what it is that they’re fighting. Because of this, these kids develop a clarity and understanding of the position they’re in that most high school students in the real world don’t. And because of the stark situations they’re put in, they’re pushed to grow and come to an understanding of themselves that they wouldn’t otherwise achieve.

Sudou’s subplot was an ideal way to introduce this kind of theme because his story mirrors that of so many people in the real world. Even if you weren’t like him yourself, I’m sure you knew someone who struggled to get results in the conventional school system. It was cathartic for me to see someone like that receive the help that even he didn’t know he needed at the time.

I get the impression that COTE will end up being the kind of story where everyone gets a turn at self-actualisation eventually. Even in the first two volumes, other characters get to experience their own striking moments of growth, like when Sakura decides to stick up for both herself and for others. But I like to think that Sudou’s story will maintain a special place in my heart even as I continue reading this series.

The world of COTE may be unfair, but it’s the kind of unfair that’s satisfying to read about.

If you liked this post, please leave a comment! However, I’m currently reading volume 3, so please don’t spoil any future developments for me! Thanks!

Victims don’t need be saints to deserve justice. You really said it there huh. Honestly you really did well to explain the introductory arc fo COTE alongside how and why it was done so.

Late reply, but thanks for the comment! :D

Great post! I am a big fan of Classroom of the Elite! Are you reading the Seven Seas editions or the Japanese ones?

Late reply, but because of the issues around alterations in the Seven Seas versions, I read the Japanese volumes. Normally I like to read the English version if it’s available, but this was a bit of an extenuating circumstance.

Interesting read. Love to see these kinds of discussions regarding cote since most discussion that I see are surface-level at best (oh this character is cute and alike) or downright toxic worst case.

Honestly, cote has no right to be this “good”, (you haven’t even gotten to the better parts yet) but something about the characters and their interactions just draws me in. I hope you keep reading this amazing series and enjoy it.

Late reply, but I’m on volume 4 right now. I took a break temporarily to catch up on other things in my backlog, but still enjoying it a lot so far! Not sure if I’ll write another post about this series since I don’t like talking about the same thing too often on this blog, but I’ll consider it if something particularly catches my eye.

I feel like my patience for this particular “the system is shitty and rigged” narrative has pretty much grown thin over the years. Granted, criticism of the “system” like this is always needed in order for improvement to be found, but I always found that these type of stories provided a very narrow, myopic point of view the “system” rather than understanding the whys and the hows of the system came about to be begin with.

It’s also why I’m often skeptical of the whole “dismantling the system” spiel because it provided a very generalized, broad-stroke view of societal problem that covers variety of factors that no person on Earth can ever have a control over, and any call toward dismantlement is a often step toward authoritarianism. It’s easy to look at flaws within a system and decided that the system is only there for the purpose of the privileged screwing over everybody else. It’s harder to look at it in terms of trade offs and compromises where not everybody can win.

So yeah, I feel like it’s more helpful to cover and review policies in case-to-case basis rather than simplistic judgement that these narratives provides.

Hmmm, maybe I didn’t explain it too well, but I don’t necessarily think of Classroom of the Elite as a story that is about dismantling the system entirely. It’s more like there’s an exaggerated hierarchy system in order to bring out the “potential” in people that wouldn’t normally come to surface in ordinary society, whether it’s their cruel side or their altruism. This impression of mine has deepened the more I’ve continued with the series; the appeal is in the mind games and character drama first and foremost.

I agree with your general thoughts that stories about dismantling terrible systems aren’t always that satisfying when they lack nuance.

One of the most things that pique your interest is that the kyotaka mentality because when I read the light novel thought bro he is fu…g frightening person ever seen like hell he knows everything.

[…] Source link […]

[…] is likely to be an excellent time to plug my literary evaluation of the primary two volumes—it’s an excellent collection from the […]

[…] pode ser um bom momento para conectar meu análise literária dos dois primeiros volumes—é uma boa série desde o […]

[…] might be a good time to plug my literary analysis of the first two volumes—it’s a good series from the […]

[…] podría ser un buen momento para conectar mi análisis literario de los dos primeros volúmenes—¡es una buena serie desde el […]