Let’s look at some of the stories that Makoto Shinkai referred to when creating Your Name. Below is a translation of a column written for the official Your Name guidebook. It’s written by Mizuo Watanabe, a manga critic and the main writer of the yearly Kono Manga ga Sugoi! guidebook.

Torikaebaya Monogatari is a classic tale about body-swapping, but at heart it’s just a story about a boy and a girl changing places at birth; their souls don’t change places.

Right from the beginning of the Your Name’s conception, the director Makoto Shinkai kept Torikaebaya in mind. In order to accurately depict a story about a boy and girl switching places, he apparently dove into a lot of different books and films. Doing this was what made him decide that he didn’t want to make a story that revolved around the differences between the sexes.

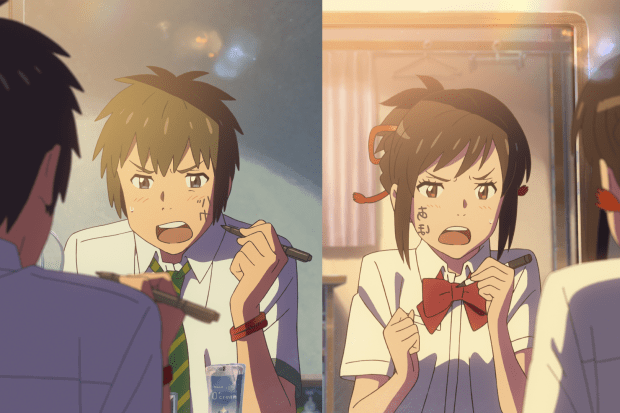

“These days, it’s normal to see boyish girls and girlish boys, so it’s hard to capture what makes the gender-bending theme of Torikaebaya so compelling,” says Makoto Shinkai. “The manga Boku wa Mari no Naka (by Shuzo Oshimi) takes a different approach. It’s a story about an unattractive college student who becomes a high school girl and is forced to see things through that perspective. What makes that story interesting is that it’s about empathising with another person’s perspective. In fact, I’d like Your Name to be kind of like Ranma ½ (by Rumiko Takahashi). One person can change into another person, and by seeing things through another person’s body, they start to understand that other person better. I hope that’s one of the main points people take away from the film.”

Shinkai also drew inspiration from the sci-fi novelist Greg Egan’s short story The Safe-Deposit Box. It’s a story about a man who wakes up in a different person’s body every day. Apparently, Shinkai also went to see the South Korean film The Beauty Inside, which is also about empathising with another person. The subtext is part of what makes the film enjoyable. I hope you take the time to enjoy all kinds of “body-swapping” stories.

Translator’s commentary: I translated this column a few months ago, but I figure it’s best to post it now that the film is finally being screened in the US.

I was really fascinated to hear that Shinkai drew inspiration from Greg Egan, an Australian novelist. I had no idea that Greg Egan was popular in Japan. Soon after translating the column, I actually went out and read The Safe-Deposit Box, which was first published in 1992 and can be found in the short story collection Axiomatic.

As what might be expected from a Hugo Award-winning author, Egan’s take on body-swapping involves no romcom or sexual shenanigans. Rather, the story is preoccupied with the concept of “ego” itself. The nameless protagonist wakes up in a different person’s body every day, and so in order to retain his sense of self, he keeps a safe-deposit box filled with memories of each of his lives.

On the surface, this doesn’t sound very much like Your Name, but I was struck by these opening lines:

I dream a simple dream. I dream that I have a name. One name, unchanging, mine until death. I don’t know what my name is, but that doesn’t matter. Knowing that I have it is enough.

Names have power. By attaching a name to something, we affix it with a sense of self. Taki and Mitsuha spend the film searching for each other, unable to put a name on what they seek. At one point, they even forget each other’s names. But this does not stop them from empathising with each other. If anything, it makes them more desperate to connect.

I’m glad that I read Watanabe’s column; it helped me appreciate why the body-swapping in Your Name is no gimmick. Shinkai evidently took care to write a body-swapping story where gender differences were beside the point. I think that’s why people found the love story between Taki and Mitsuha so affecting despite the fact that they only interact directly, like, once in the entire film. They learned to see the world through each other’s eyes, and isn’t that the most important thing?

Oh goody, I’m about to see the film right this second! I’ll keep Shinkai’s influences in mind as I ponder the whole body swapping thing. I’ve also seen a lot about the “splitting motif”, so I guess I’m most excited about that.

Hope you enjoyed the film!

Interesting. I might try to watch Your Name again at some point and see if it works better for me next time.

Hopefully! Although I understand it’s not for everyone.

[…] What We Learn Through Body-swapping: The Subtext of Torikaebaya and Your Name (Fantastic Memes) […]

I think I can see where he was going with this for the first two acts, but I think the condensation of it into a montage sort of glances over all of it. I mean it hits a lot of the better points for the most part, how a different personality changes the perceptions of the people around either one of them, and how they can never truly imitate the other. I kind of wish to have seen more of Taki’s world explored. I felt that side was not really developed.

Yeah, the lack of focus on Taki’s background was disappointing. You know his parents are divorced and he’s kinda distant from his father, but that’s about it. I don’t think the Earthbound spinoff novel goes into much detail about him either.

I was wondering about his living arrangement as well. Didn’t really catch the divorce part, must have been part of that flashback. I think that first guy Mitsuha sees was a roommate even. I think there needed more emotional buildup for this relationship compared to that third act.

[…] What We Learn Through Body-swapping: The Subtext of Torikaebaya and Your Name (Fantastic Memes) […]

Reblogged this on thecityhearsyou.

Overall, I really enjoyed the film, but there are just a few little things that betray Shinkai’s intention to get away from “the difference between sexes,” probably invisible to Shinkai’s perception.

Most notably, of course, is the boobs gag, which I appreciated on a structure/craft level, but nonetheless was a little bit irritating. (A nice subversion of that would be to have Mitsuha be the one dealing with morning wood every time. Or, to avoid a sexual joke entirely, have the gag be Yotsuha witnessing Taki dealing with long hair in weird ways.)

More interestingly, a lot of the framing choices for Taki’s body’s scenes with Miki portrayed a hormonal reaction (even when Mitsuha was in control) in a way we never saw in Itomori.

And, finally, although Mitsuha gets the ultimate “saving” action of convincing her father, that catharsis is left offscreen and unseen by the audience (though I understand how that’s a compelling way of portraying the story), and we don’t see the way she’s been impacted in the aftermath. She’s gone to Tokyo as she desired to at the beginning of the movie, and we have no sense of parallel change to match Taki’s desire to cherish landscapes and to convey that joy to others. Mitsuha has become a bit more of a cipher by the end of the film than in the first act.

Interesting to see some of the gendered assumptions that Shinkai makes even when he’s not trying to make them.

I agree. The boob thing felt out of place, even if it was pretty funny. As for that last act, I believe that the lives of the characters become harder to read in order to build up tension. “Will they or want they?” is a question with genuine uncertainty in a Shinkai film where the answer is usually no. The framing makes sense and it certainly keeps you guessing about the couple’s ultimate fate, but it does undermine the themes a bit.

I can’t help but be moved by what this film sets out to accomplish, though, because it does so much else right.

Yes, anime does life-affirming catharsis like nobody’s business, and Your Name certainly delivered on that. Even though we don’t see that actual conversation between Mitsuha and her father, the film mostly pays that off, in the montage of Mitsuha running bursting into his office, showing the slight differences of when Taki confronted him.

Another theme that the film does really well is that of agency and faith. The body-swap takes control away from Taki and Mitsuha, but they take steps to adapt and even enjoy their new situation. Mitsuha chooses to share her phone number with Taki, and Taki chooses to call her.

Then, when body swapping is taken away from them, Taki, Mitsuha, Teshi, and Sayak all make choices not to be complacent in their new situation, even though they don’t have certainty about the future.

And, finally, the ending, where Taki and Mitsuha choose to follow their instincts against propriety, and reach out to a stranger.

This is paralleled with growing up. The body-swap mirrors the uncertainty about our changing bodies in adolescence, but a part of maturity is going forward with making choices anyways. Compare to the relative complacency Mitsuha had about her life at the start of the film. Her decision to visit Tokyo mirrors how her father chose to leave the priesthood and choose to try to improve the town, instead of letting things be. Mitsuha is able to connect with her father at the key time because she has become more adult.

It’s very odd that even thought I write genderbender for the purpose of “examining the other side’s perspective” (and I did notice that for Kimi no na wa), I’ve never seriously considered this for bodyswapping…

Very informative article that’s been thought provoking… thanks ^^

You said in your first Your Name post that you had a personal connection to the film, but didn’t want to spoil it since many still hasn’t seen it. Isn’t it about time now?

Yes, but now that I think about it, it’s kind of hazukashii